When smart students are failing med school, “diagnosing” the issues must look at internal and external factors

By Dr. Jim Culhane, Assistant Dean for Student Academic Success Programs and Professor of Pharmaceutical Sciences at Notre Dame of Maryland University School of Pharmacy

“I’m failing med school (or pharmacy, veterinary, etc.) — and I don’t know why!

As an academic coach and faculty member for almost 25 years, I’ve frequently heard this sentence from struggling pharmacy students at the proverbial “end of their rope.” They’ve tried everything they can think of (study harder, study longer, get a tutor, meet with their professor, etc.), but their bad grades persist. Why do these smart students perform poorly in health professions programs, especially if they could navigate their undergraduate degree programs with success and ease?

Developing a formula that accurately predicts how a student will perform in an academic program is extremely difficult. The variables impacting student learning and academic success are incredibly complicated and personalized. When students struggle, it is critical to get help quickly as their education and future career often depends on it.

Unfortunately, finding help and concrete solutions to their problems is often difficult. If you are fortunate enough to find a staff or faculty member at your school that is willing to listen, they may not have the appropriate training or insight to diagnose and address your learning issues. Ryan, Dave, and I have heard many horror stories over the years from struggling students who were told that they weren’t cut out to be a (doctor, pharmacist, veterinarian, PA, etc.) because they lacked work ethic, motivation, or intelligence. Worse yet, they received terrible, reductionist advice that implied their attitude, ability to self-regulate, or motivation was the issue.

In these cases, students might hear advice like:

- “Work harder.”

- “Study more.”

- “Sleep less.”

- “Maybe you should consider an alternate career.”

- “You aren’t cut out to be a (doctor, pharmacist, veterinarian, PA, etc.).”

There are situations where the issues outlined above are part of the problem. Other times, tough love conversations about future career plans need to happen. Being in a health profession isn’t for everyone, and these programs are challenging for a reason. But educators and students need to be careful about deciding to end an academic career without taking the time to ensure the challenges they face are intractable. I have found, in many cases, they are not.

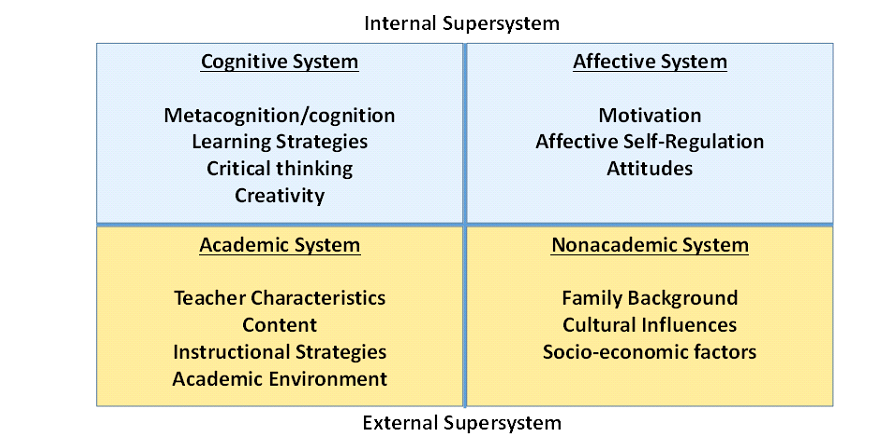

It is very clear from the research that the variables underpinning academic success are way more complicated than how hard you work or your motivation. When “diagnosing” issues with struggling students, I rely on the BACEIS (Behavior, Affect, Cognition, Environment Interacting Systems) model developed by Hartman and Sternberg. 1,2 As seen in the picture below, the BACEIS model categorizes variables that impact learning into external and internal supersystems. All this means is that things outside of the student and internal to the student can impact their ability to learn. Within each of these supersystems are two subsystems and examples of specific components. This model’s comprehensive nature helps keep all the aspects impacting student learning in front of me. This helps avoid developing tunnel vision and falling into the reductionist trap mentioned above.

External supersystem factors identified in the BACEIS model are primarily associated with academic and nonacademic environments. Examples of factors in your academic system include the content you are learning, the instructor teaching you, the teaching and learning strategies used and your general learning environment. Nonacademic environment examples include socio-economic status, cultural influences, and family background.

Often, struggling students may have little or no control over these factors, and they may need to develop skills and approaches to learning that compensate for them.

Internal supersystem factors representing the cognitive system include cognition, metacognition, critical thinking, creativity, and learning strategies employed by the student. Additionally, the affective domain includes:

- A student’s ability to self-regulate their feelings.

- Their locus of motivation.

- The attitudes they bring to learning.

Many factors represented by this supersystem can be developed and enhanced in students. For many, this is the key to improving their learning and academic performance. In part two of this blog post, we look closely at the external supersystem and related factors, examples of how they can impact learning, and potential solutions.

Interested in learning more about how we can help you improve your study habits and the way you approach medical education? Check out the STATMed Study Skills Class!

Ready to improve your studying and get better results? Get in touch!

- 1Hartman H. Metacognition in Learning and Instruction. Kluwer Academic Publishers; 2001.

- 2 Hartman H, Sternberg RJ. A Broad BACEIS for Improving Thinking. I. Instr Sci. 1993;21:401-425.